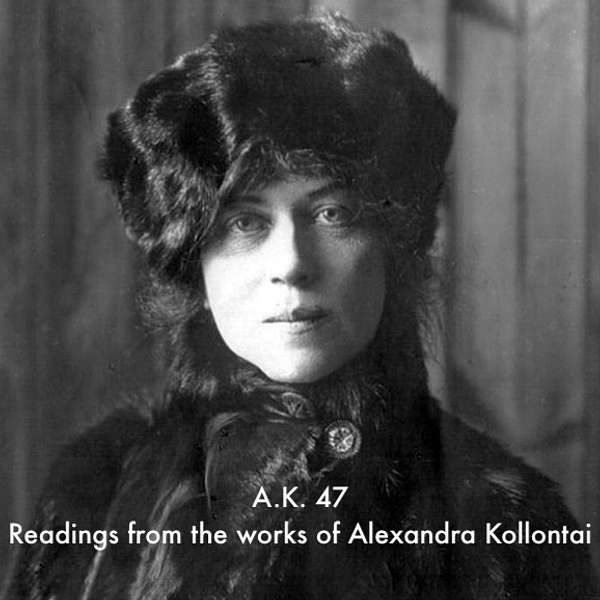

A.K. 47 - Selections from the Works of Alexandra Kollontai

Kristen R. Ghodsee reads and discusses 47 selections from the works of Alexandra Kollontai (1872-1952), a socialist women's activist who had radical ideas about the intersections of socialism and women's emancipation. Born into aristocratic privilege, the Ukrainian-Finnish Kollontai was initially a member of the Mensheviks before she joined Lenin and the Bolsheviks and became an important revolutionary figure during the 1917 Russian Revolution. Kollontai was a socialist theorist of women’s emancipation and a strident proponent of sexual relations freed from all economic considerations. After the October Revolution, Kollontai became the Commissar of Social Welfare and helped to found the Zhenotdel (the women's section of the Party). She oversaw a wide variety of legal reforms and public policies to help liberate working women and to create the basis of a new socialist sexual morality. But Russians were not ready for her vision of emancipation, and she was sent away to Norway to serve as the first Russian female ambassador (and only the third female ambassador in the world). In this podcast, Kristen R. Ghodsee – a professor of Russian and East European Studies at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism: And Other Arguments for Economic Independence (Bold Type Books 2018) – selects excerpts from the essays, speeches, and fiction of Alexandra Kollontai and puts them in context. Each episode provides an introduction to the abridged reading with some relevant background on Kollontai and the historical moment in which she was writing.

A.K. 47 - Selections from the Works of Alexandra Kollontai

2 - A.K. 47 - Women's Day 1913

In this first episode, Kristen Ghodsee provides and introduction and reads an abridged version of Alexandra Kollontai's 1913 article in Pravda. Published on March 8 (February 23 in Russia), this essay addresses concerns that celebrating an international women's day could be seen as a concession to the "bourgeois feminists."

Kristen R. Ghodsee is a Professor of Russian and East European Studies at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism: And Other Arguments for Economic Independence. More information about Kristen R. Ghodsee can be found at www.kristenghodsee.com

Thanks so much for listening. This podcast has no Patreon-type account and receives no funding. There are no ads and there is no monetization. If you'd like to support the work being done here, please spread the word with your networks.

Kristen R. Ghodsee is the award-winning author of twelve books and Professor of Russian and East European Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. Check out Kristen Ghodsee's recent books:

Subscribe to Kristen Ghodsee’s free, episodic newsletter at: https://kristenghodsee.substack.com

Learn more about Kristen Ghodsee's work: www.kristenghodsee.com or request to follow her on Instagram @prof_kristen

Excerpt from The Internationale

Kristen Ghodsee:Hello. My name is Kristen Ghodsee and this series of recordings is something that I'm going to call A.K. 47, which is 47 readings from the works of Alexandra Kollontai who was a Russian socialist feminist who wrote in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. She was also the first commissar of social welfare in the Soviet Union after the Bolshevik revolution in 1917 and she had a lot of interesting thoughts and opinions about the role of women in the revolution and the role of socialism in creating women's emancipation. So to kick off this series, I'm going to be reading a piece called"Women's Day" from 1913. It was published on International Women's Day– March 8th or February 23rd depending on where you are– and this was an address(four years before the revolution) to the working women of Russia. So the context of this essay, which was published in Pravda in 1913, is the division between working class women and what she calls"bourgeois feminists." It's very important to understand that Alexandra Kollontai herself despised the feminists. She thought that they were actually working against the interests of the working class. And the reason that she thought this was because the so-called bourgeois feminists or suffragettes were basically advocating for the right to vote, but also for certain property rights for women, laws, rights of inheritance, and rights to enter professions that had previously been closed to them. Kollontai believed that these upper-middle-class and middle-class women were essentially trying to expand privileges for themselves, to gain equality with the men of their class while leaving their working class sisters behind. So the charge of being a"feminist" would have been a very stinging charge against somebody like Kollontai, who really saw herself primarily as a socialist. It's important to remember that Kollontai herself was initially a Menshevik and she was very close with the Social Democratic Party in Germany. And it's only after the onset of World War I that she becomes a Bolshevik, largely in response to WWI because of her pacifist position against the war. So the problem that Kollontau faces in advocating for something like International Women's Day is that to her male colleagues, it sounds like she's advocating for a separate organization for women, a separate movement for women. And the idea of a separate organization for women, or a separate movement for women, is completely opposed to her own ideas about how the working class should be united in its struggle against capital. But Kollontai in this article argues that there does need to be special attention paid to women because of their roles, specifically as mothers and as caregivers for the family. Women have different needs than men do because of these responsibilities in the home. And they need to be appealed to not only as workers, but also as mothers. And Kollontai doesn't see this as a contradiction. In fact, she very strongly believes that the socialization of domestic work will liberate women and that it should be squarely on the socialist agenda even as early as 1913 before, you know, there's even a hint of the Bolsheviks coming into power. So this is an article addressed primarily to Russian women. And it's saying, yes, it's okay to participate in a holiday like International Women's Day because it is supporting the unity of the working class. But it's also, I think, addressed to men in her party, men in the workers' movement who are perhaps a little bit nervous about this idea of women having their own special day and their own special publications. And she's calming them down and saying:"no, we have to radicalize women." The movement will be stronger with them. And the way to do that is to appeal to them around their roles as mothers and as caregivers for the family. And that that kind of language is not going to appeal to male workers. And so there is a special need to kind of meet women on their own terms. And so this piece of writing is essentially a way of arguing that even though International Women's Day is a special day set aside for women, it is in no way going to divide the strength of the working class movement. And if anything, it's going to create greater unity and greater power in the long run. So without further ado,"Women's Day" from International Women's Day on March 8th or February 23rd, 1913, this is Alexandra Kollontai published in the newspaper Pravda.

A. Kollontai:What is women's Day? Is it really necessary? Is it not a concession to the women of the bourgeois class, to the feminists and suffragettes? Is it not harmful to the unity of the workers' movement? Such questions can still be heard in Russia. They are no longer heard abroad. Life itself has already supplied a clear and eloquent answer. Women's Day is a link in the long solid chain of the women's proletarian movement. The organized army of working women grows with every year. Twenty years ago, the trade unions contained only small groups of working women scattered here and there among the ranks of the Worker's Party. Now, English trade unions have over 292,000 women members in Germany around 200,000 are in the trade union movement and 150,000 in the Workers Party. And in Austria there are 47,000 in the trade unions and almost 20,000 in the party. Everywhere in Italy, Hungary, Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Switzerland, the women of the working class are organizing themselves. The women's socialist army has almost a million members, a powerful force, a force that the powers of this world must reckon with when it is a question of the cost of living, maternity insurance, child labor and legislation to protect female labor. There was a time when working men thought they alone must bear on their shoulders the brunt of the struggle against capital, that they alone must deal with the old world without the help of their womenfolk. However, as working class women entered the ranks of those who sell their labor, forced onto the labor market by need and by the fact that husband and father is unemployed, working men became aware that to leave women behind in the ranks of the non-class conscious was to damage their cause and hold it back. The greater the number of conscious fighters, the greater the chance of success. What level of consciousness is possessed by a woman who sits by the stove who has no rights in society, the state or the family. She has no ideas of her own. Everything is done as ordered by the father or husband. The backwardness and lack of rights suffered by women, their subjection and indifference, are of no benefit to the working class and indeed are directly harmful to it. But how is the woman worker to be drawn into the movement? How is she to be awoken? Social Democracy abroad did not find the correct solution. Immediately workers, organizations were open to women workers, but only a few entered. Why? Because the working class at first did not realize that the woman worker is the most legally and socially deprived and member of that class, that she has been brow beaten, intimidated, persecuted down the centuries, and that in order to stimulate her mind and heart, a special approach is needed. Words understandable to her as a woman. The workers did not immediately appreciate that in this world of lack of rights and exploitation, the woman is oppressed not only as a seller of her labor, but also as a mother, as a woman. However, when the Workers' Socialist Party understood this, it boldly took up the defense of women on both counts as hired worker and as woman, as a mother. Socialists in every country began to demand special protection for female labor, insurance for mother and child, political rights for women, and the defense of women's interests. The more clearly the Worker's Party perceived this second objective, vis a vis women workers, the more willingly women joined the party and more they appreciate it that the party is their true champion, that the working class is struggling also for their urgent and exclusive female needs. Working women themselves, organized and conscious, have done a great deal to elucidate this objective. Now the main burden of the work to attract more working women into the socialist movement lies with women. The parties in every country have their own special women's committees, secretariats, and bureaus. These women's committees conduct work among the still largely non-politically conscious female population, arouse the consciousness of working women and organize them. They also examine those questions and demands that affect women most closely: protection and provision for expectant and nursing mothers. The legislative regulation of female labor, the campaign against infant mortality, the demand for the political rights for women, the improvement of housing, the campaign against the rising cost of living, etc. Thus, as members of the party, women workers are fighting for the common class cause while at the same time outlining and putting forward those needs and demands that most nearly affect themselves as women, housewives, and mothers. The party supports these demands and fights for them. The requirements of working women are part and parcel of the common workers' cause. On Women's Day the organized demonstrate against their lack of rights. But some will say, why this singling out of women workers? Why a special Women's Day, special leaflets for working women, meetings and conferences of working class women? Is this not in the final analysis, a concession to the feminists and bourgeois sufferagettes? Only those who do not understand the radical difference between the movement of socialist women and bourgeois suffragettes can think this way. What is the aim of the feminists? Their aim is to achieve the same advantages, the same power, the same rights within capitalist societies, those possessed now by their husbands, fathers and brothers. What is the aim of the woman workers? Their aim is to abolish all privileges derived from birth or wealth. For the woman worker, it is a matter of indifference who is the master, a man or a woman. Together with the whole of her class, she can ease her position as a worker. Feminists demand equal rights always and everywhere. Women workers reply:"We demand rights for every citizen, man and woman, but we are not prepared to forget that we are not only workers and citizens, but also mothers. And as mothers, as women who give birth to the future, we demand special concern for ourselves and our children. Special protection from the state and society. The feminists are striving to acquire political rights. However, here too our paths separate. For bourgeois women, political rights are simply a means allowing them to make their way more conveniently and more securely in a world founded on the exploitation of the working people. For women workers, political rights are a step along the rocky and difficult path that leads to the desired kingdom of labour. The paths pursued by women workers and bourgeois suffragettes have long since separated. There is too great a difference between the objectives that life has put before them. There is too great a contradiction between the interests of the woman worker and the lady proprietress, between the servant and her mistress.There are not and cannot be any points of contact, conciliation or convergence between them. Therefore working men should not fear separate Women's Days, nor special conferences of women workers, nor their special press. Every special, distinct form of work among the women of the working class is simply a means of arousing the consciousness of the woman worker and drawing her into the ranks of those fighting for a better future. Women's Days and the slow, meticulous work undertaken to arouse the self-consciousness of the woman worker are serving the cause not of the division but of the unification of the working class. Let a joyous sense of serving the common class cause and of fighting simultaneously for their own female emancipation inspire women workers to join in the celebration of Women's Day.

Kristen Ghodsee:So that was Alexandra Kollontai from 1913 addressing Russian women on the holiday of International Women's Day, which is March 8th. This is the first of my recordings. I am pretty much a Newbie and trying to learn how to do this. But if you like this podcast or series of recordings– I'm not really sure what I'm calling it– I guess it's a podcast, please subscribe and let other people know about it if they're interested in learning about the origins of socialist feminism or interested in learning about Alexandra Kollontai or just interested in thinking about women's rights from a leftist perspective. Thanks so much for listening. And until next time, this is Kristin Ghodsee reading 47 selections of the works of Alexandra Kollontai on the AK 47 podcast.